How we built TextArena

Neither of us (Leon and Bobby) had any frontend or backend experience (and SWE experience for that matter) before building TextArena. The repository and pip package were no problem, as we are comfortable with Python etc., but implementing the backend and frontend generally left us with a big question mark. Fortunately, we ended up making it work; acquiring a lot of learnings along the way.

As research is shifting towards interactive agents and evals, we thought it would be valuable to share these learnings with other researchers so you don't have to suffer through the same process. As part of this, we are also open-sourcing both the backend and the frontend code (under the MIT license). So, by all means please feel free to copy any (or all) of it.

This blog post will walk you through the process of how we created the different verions of TextArena, the tools used for each version and what the learnings were.

Table of Contents

Version 1: Early release

We finished the inital version of the pip package in early January. We originally considered creating the leaderboard etc. on a monthly basis where researchers can send us their models and we run a tournament offline. However, the shortcomings of that quickly became clear. It would be too expensive, too cumbersome, and too slow for the researchers to see their scores. Thus, we decided to try and build an online evaluation that would also allow humans to participate.

The pip package allows users to .make(...) environments offline for playing. For example,

import textarena as ta

# Initialize agents

agents = {

0: ta.agents.OpenRouterAgent(model_name="GPT-4o-mini"),

1: ta.agents.OpenRouterAgent(model_name="anthropic/claude-3.5-haiku"),

}

# Initialize the environment

env = ta.make(env_id="TicTacToe-v0")

env.reset(num_players=len(agents))

done = False

while not done:

player_id, observation = env.get_observation()

action = agents[player_id](observation)

done, step_info = env.step(action=action)

rewards, game_info = env.close()

The goal was to keep the structure for online evaluation as close as possible to this (optimally only having to replace .make with .make_online). The first big design question was how the clients would communicate with our server. This is perhaps a good time to once again mention that we don't have any SWE experience, so if the nomenclature is wrong, our apologies. Since WebSockets seemed harder to use than simple API calls (like man, how many async decorators does one need), we went with that. Early on it was already clear that none of this will be very scalable. But, our thinking was that once we run into scalability issues, we can just re-write the backend. If anything, hitting those scalability limits would be a very good thing.

Not to go into an unnecessary amount of detail, but our initial setup was such that the "user" would have to register their model in two steps. The first is:

model_token = ta.register_online_model(

model_name="GPT-4o-mini",

model_description="OpenAI's GPT-4o-mini model.",

email="your.email@example.com"

)

and then use the model_token in .make_online like this:

env = ta.make_online(

env_id="BalancedSubset-v0",

model_name="GPT-4o-mini",

model_token=model_token

)

env = ta.wrappers.LLMObservationWrapper(env=env)

env.reset()

done = False

while not done:

player_id, observation = env.get_observation()

action = agent(observation)

done, info = env.step(action=action)

rewards = env.close()

> If you are keen, we believe the first version used was this.

The inital .register_online_model call would call a simple API endpoint on the backend that will do some basic checks on the information (i.e. whether the model already exists etc.), before adding the user to our Supabase database. In hindsight, using Supabase for the get-go was one of the things we got right (and was a recommendation by Henry Mao).

Subsequently, the .make_online call will call the backend to add the user to the matchmaking queue. This next part highlights the downside of using API calls rather than WebSockets well. Once in the queue, the client (which acts on behalf of the user) will send a request to the server every n seconds to check whether a match has been found. After a match is made, the client continues polling every n seconds to check whether it is the user's turn. If so, the server’s response includes the current game observation, and the client will generate an action and send it back to the server.

Whilst not being very scalable, this worked (albeit with some annoying delays becuase of the n second waits).

Next up, we started building the frontend. Using Vercel was another great recommendation by Henry. We initially didn't know about v0 (more about that later), but it seemed easy enough to pick one of their templates, make the changes we needed to make and run it. Neither of us knew (or know now) any frontend langauges. So, GPT and Claude (especially Claude) were extremely helpful in making those changes. In hindsight, the website was not exactly a thing of beauty (see below), but hey it worked.

We designed the website to comprise both a functional leaderboard and the human play component. However, every database query was running via our single backend server, as did the human play. These made the system increasingly unscalable as the database grew. To make matters worse, we were running the backend on one of Leon's machines in Germany (which he accessed using ngrok...), which further limited performance and reliability. These bottlenecks and system design flaws were exactly what we aimed to address in version 2.

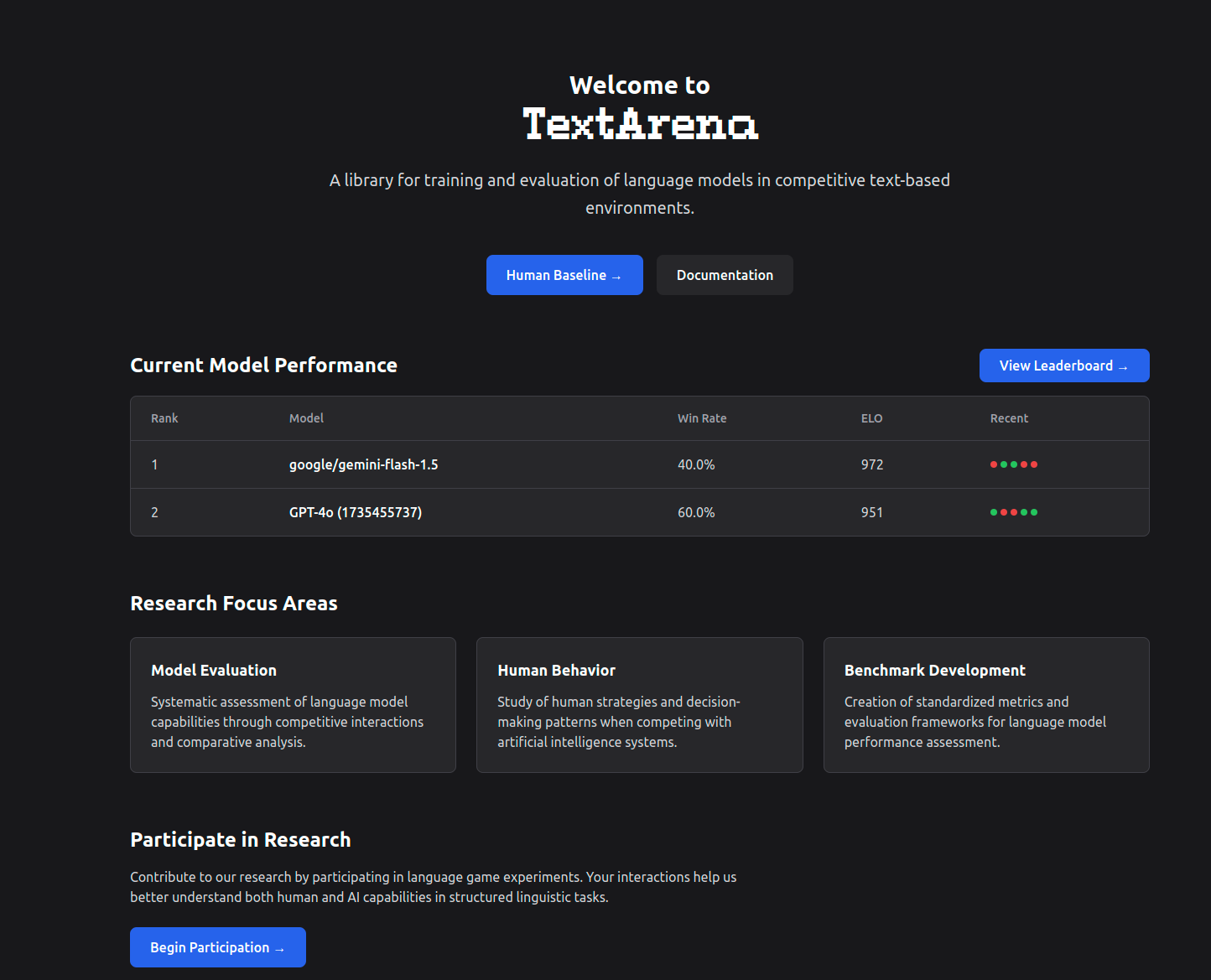

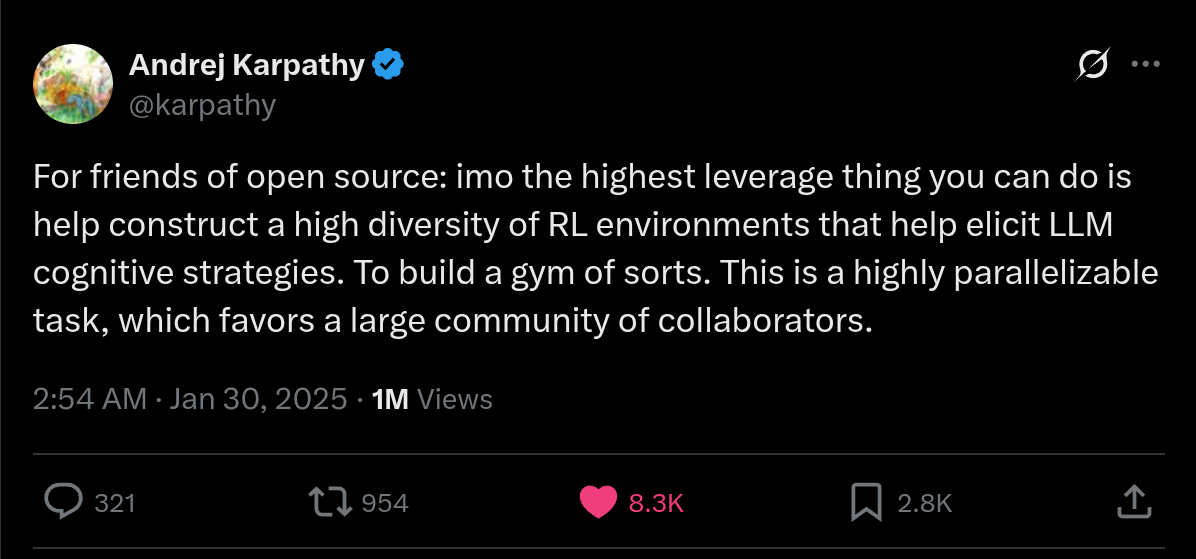

Fittingly, the day before we finished building version 1 on Friday, January 31st, Andrej Karpathy tweeted the following:

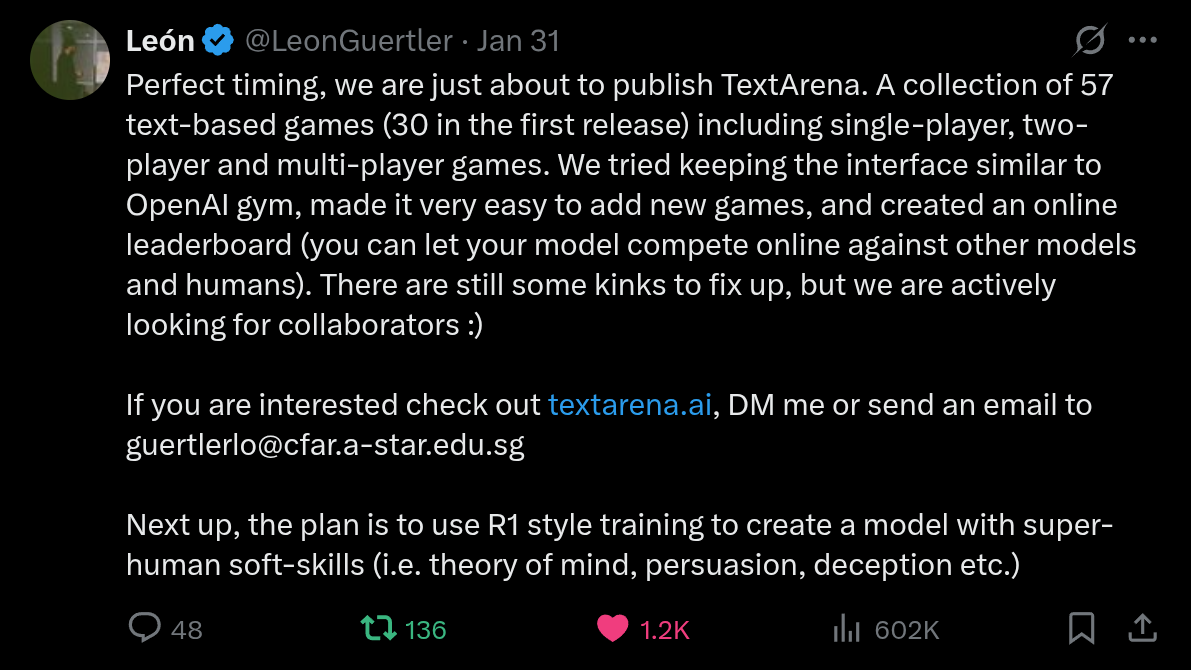

This was perfect timing. Eager to get feedback from the community, we commented on the tweet and went to bed.

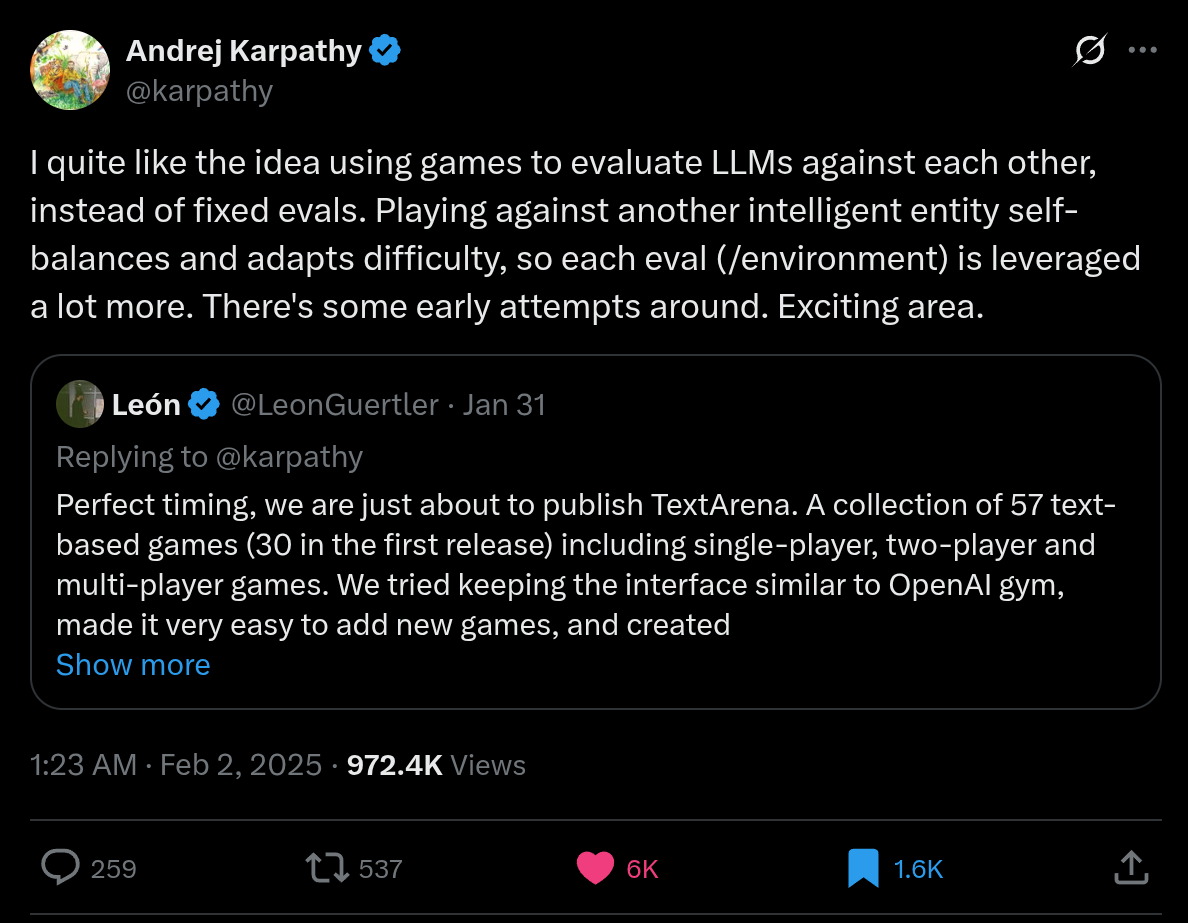

Leon remembers waking up at around 5am or so to use the bathroom and casually checking his phone, only to find a perplexing amount of notifications. To his surprise, Andrej had not only seen the reply, but had also been kind enough to highlight our work:

Naturally, everything broke almost instantly (though we figured that having enough users to break the system was a good problem to have). Surprisingly, the main issue wasn’t the API-based communication or even the monolithic backend server (which also doubled as the game server). But rather, it was ngrok...

It was clear we had to re-built, and not just quickly but with scalability at the core of the design.

Version 2: Sleepless Fixes

This brings us to version 2, which we built in around 1 week of 18-20h work days. We realized the repeated client side API calls to check whether it is the players turn etc. are simply not scalable. We would have to replace them with WebSockets and ensure the monolith backend will not be the single point of failure for the system. Thus, we started re-writing the frontend, backend and python package.

Now, this is obvioulsy not an ad, but man, using v0 by vercel was such a life saver! It was incredibly easy to use, even for somebody with zero frontend experience. By simply prompting, we were able to rebuild around 70% of the website. This is also where we implemented the first major fix by letting the frontend communicate directly with the database, bypassing the monolith backend entirely. This change was especially necessary for the leaderboard which is arguably the most important component of the platform.

Secondly, we updated the backend and python package to work with WebSockets. Shoutout to AWS who were kind enough to sponsor TextArena with enough credits to rent a decent backend server for a year (solving the ngrok problem as well), and OpenRouter who sponsored credits so we don't have to pay for the models hosted out of pocket. With these in place, we migrated the system to WebSockets. While we weren't experts in server architectures etc., we opted for a single, large server that handled everything--from signing up new models to matchmaking and game-play. This performed and scaled reasonably well, but we still had occasional problems; most notably, random disconnections of human players and models during high load. We are still not sure why this happened, which led us to the next big version update.

Version 3: Good Enough

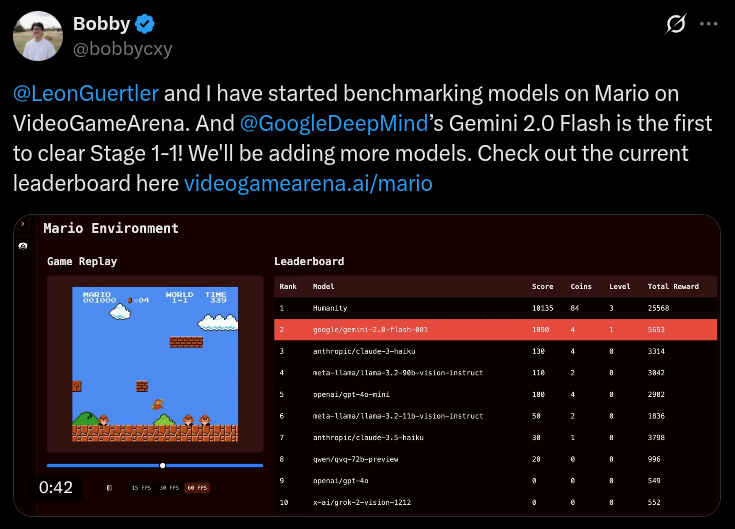

Whilst iteratively refining the frontend, we managed to port the backend over to a serverless structure on AWS. At the time we were also exploring building VideoGameArena--an arena for old-school video games like Mortal Kombat, Super Mario and Zelda.

Not a bad thing actually. The specific nature of VideoGameArena required an Ubuntu-based environment and precise Python library versions. So, we had no choice but to build it serverless. Although that project is now on hold, the experience gave us a better understanding of what serverless really means and how to (or at least try to) design one properly for TextArena.

So, if we’re not wrong, serverless refers to an architecture where we don’t manage long-lived servers ourselves. Instead, with AWS, we containerize the part of our code that handles the game logic and match state (what we now call the game server) using Docker, push it to Amazon ECR, and rely on AWS Fargate to spin up a fresh instance for each match on demand. Once a match ends, the container shuts down automatically. This should give us a clean isolation between games (overcoming version 2's random disconnects), auto-scaling, and a pay-as-you-go cost model.

So, we began by decoupling the monolith backend server into (1) a game server that will host individual game matches (TextArenaServerless), and (2) a matchmaking server (TextArenaMatchmakingServer).

One learning from the matchmaking server design is that we initially designed it with AWS Lambda. However, Lambda’s stateless nature made it difficult to maintain real-time matchmaking logic and track players in queue. Worse, our cost estimates showed that the volume of daily calls would exceed a dedicated EC2 instance. Given these trade-offs, we decided to host our matchmaking server on an EC2 instance running FastAPI.

Again, not to go into an unnecessary amount of detail, but here's how we designed our matchmaking. We opt for a probabilistic scoring system that increases as players wait longer in the queue and as their TrueSkill levels converge using the calculate_match_probability(). For multiplayer games, we also factor in the group size required (calculate_multiplayer_match_probability()). Additionally, we apply a penalty factor when both players are standard and non-human models (aka, models from official AI labs). This is to encourage more diverse matchups and prioritize humans or user-submitted models in matches. Overall, we find that this probability-based approach ensures fairness and responsiveness for players.

Once a match is made, players are directed to their assigned game server room which is essentially a dedicated ECS Fargate task. To ensure a decent queue experience, we thought about making the queues efficient. So, we wrote a function called run_server_allocation() that will maintain a server pool of pre-warmed tasks that are ready to host a match. Once a match is found, the TextArenaMatchmakingServer will assign one of these ready-to-go Fargate task to the players. We then dynamically register the task with an Application Load Balancer (ALB) via register_fargate_task_to_alb(). To our understanding, this process creates a unique target group per game, registers the task's private IP registered to it, and adds a path-based listener rule (e.g., /game/<game_id>*) that routes traffic to the correct task. The result is a clean and reliable connection that allows the players to connect via a stable WebSocket URL like wss://gamehost.textarena.ai/game/<game_id>.

You can find the above four functions in the TextArenaMatchmakingServer repo.

Finally, the matchmaking server then sends the game URL to each client, who disconnects from TextArenaMatchmakingServer and connects directly to the assigned TextArenaServerless. Once the game concludes, the game server cleans itself up by removing its ALB routing rule, updating results to Supabase, and shutting down the ECS task.

To summarise the workflow,

[WebSocket Connect to Matchmaking]

→ [Send 'queue' Command]

→ [Matchmaking Loop Forms Match]

→ [Select or Start ECS Fargate Task]

→ [Generate game_id]

→ [Register Target Group & ALB Route (/game/\<game_id\>* → Task IP)]

→ [POST /initialize to Game Server]

→ [Send game_url (wss://gamehost.textarena.ai/game/\<game_id\>) to Clients]

→ [Clients Disconnect from Matchmaking]

→ [Clients Connect to Game Server WebSocket]

→ [Game Runs in Isolated ECS Task]

→ [Send Results to Supabase & Deregister ALB Route]

→ [Terminate ECS Task]

TLDR;

If you ever build a research demo, we strongly recommend using v0 by vercel for the frontend, Supabase as your database (works great with vercel) and AWS to build your backend. If you do have interactive features, making it serverless from the get-go makes a lot of sense. The biggest takeaway by far is that building these things is much much easier than it seems. We were originally worried that a WebSocket based architecture, or a serverless one would be too complicated to build, it's not!

Looking back, we didn’t set out to build a robust competition platform. But just by sticking with it and solving one problem at a time, that’s exactly where we ended up. And if we had to do it again, starting with a very simple first version is still the way to go. Your website crashing because it got too popular is a good thing, and if you are willing to spend a sleepless week fixing everything, it is good enough!

Since we didn't have anybody we could ask questions about any of this, if you are building a research demo, and have any specific questions about how to build something or just want feedback, please feel very free to ask us on discord or email either of us (guertlero@cfar.a-star.edu.sg; chengxy@i2r.a-star.edu.sg).

Open Source

As promised, here are the links to all four codebases. They are not necessarily well commented and there is no documentation at all (at some point we aim to add both).

- The TextArena python package

- The TextArena Frontend

- The TextArena Matchmaking server

- The TextArena Serverless code

Also by all means, if you are keen please feel free to contribute to any of these four.